WUSD Board of Education members attend open meeting, public records laws workshop

- Home

- WUSD Board of Education members attend open meeting, public records laws workshop

WUSD Board of Education members attend open meeting, public records laws workshop

Editor’s note: Members of the Whitewater Unified School District Board of Education, in advance of their regularly scheduled July monthly board meeting, attended an hour-long workshop presented by the district’s attorney, Brian Waterman, of the Waukesha-based firm Buelow Vetter Buikema Olson and Vliet, LLC (Buelow Vetter). Information shared during the workshop came in three parts: open meetings law, public records law, and school board operations. Following is the first of a three-part story about information shared during the workshop.

By Kim McDarison

Members of the Whitewater Unified School District Board of Education recently attended a workshop offering information about Wisconsin’s open meetings and public records laws. The workshop was held earlier this month at the Whitewater High School in advance of the board’s regularly scheduled July meeting.

The workshop was conducted by the district’s attorney, Brian Waterman, of the Waukesha-based firm Buelow Vetter, and offered three topics of discussion: open meetings law, public records law, and school board operations.

Board of Education President Larry Kachel, in advance of the workshop, told WhitewaterWise’s sister publication, Fort Atkinson Online, that the workshop was scheduled to help new board members better understand the laws.

Three board of education members, Stephanie Hicks, Christy Linse and and Lisa Huempfner, were elected in April.

Open meeting law

Aided by a 24-page handout, Waterman began his presentation by quoting from state statutes, offering the “policy of the state,” which, he said, declares “that the public is entitled to the fullest and most complete information regarding affairs of the government as is compatible with the conduct of government business.”

He further quoted: “All meetings of all state and local governmental bodies shall be publicly held in places reasonably accessible to members of the public and shall be open to all citizens at all times unless otherwise expressly provided by law.”

Offering an interpretation of the law, Waterman said that every meeting of a governmental body must be preceded by a public notice and initially convened in open session.

Additionally, he said, the state’s open meeting law is “liberally construed,” meaning that any doubts about a meeting’s adherence to exemptions to open meeting laws “should be resolved in favor of openness.”

Waterman next offered a definition of “governmental body,” defining the term as a state or local agency, board, commission, committee, council, department or public body corporation and politic created by constitution, statute, ordinance, rule, or order …”

Such entities meet for the purpose of exercising their authorized responsibilities, authority, power or duties delegated to or vested in the body,” he said, quoting from statutes.

“There must be a purpose to engage in governmental business,” Waterman said, adding that only a board has the authority to engage in governmental business and not the individual board members, whom, he noted, have no authority to act or speak on behalf of the board unless the board authorizes them to do so.

Within his presentation, Waterman said at least one half of a board’s membership, known as “a quorum,” must be present at a meeting in order for the board to “rebuttably” conduct business.

An existence of a quorum, in any form, would constitute a meeting to which open meeting laws would apply.

He further defined a “negative quorum” as existing when half of the body’s members meet and possess the “power to defeat action taken by the governmental body.”

A “walking quorum,” he said, is created when a board member conducts conversations with other board members, holding those discussions as a group, or with individual members each in turn, to negotiate the public’s business.

He pointed to communication forms, such as texts, emails, and shared document drives, as falling within the definition of a walking quorum.

Board members are able to share relevant information pertaining to an item of board interest, he said, but such information should be shared with all board members and the district’s superintendent, and board members should not reply to such communications.

Under a heading of “open session” Waterman said the state’s open meeting laws permit, but do not require, that bodies provide a period for public comments.

However, if a public comments period is offered, members of the body should refrain from deliberating or taking action on items raised during public comment sessions, opting instead to place applicable items on a future agenda.

Additionally, he said: “The public comments section of board meetings does not provide flexibility for board members to bring up items not specifically designated on the posted meeting notice.”

Under a heading of “closed session,” Waterman told the board that they, as elected officials, may exercise their right to convene into closed session, but only for one of the reasons specified within state statutes.

Requirements of a closed session, he said, include an announcement made by the chief presiding officer to all those present of the body’s intention to move into closed session; a statement from the chief presiding officer about the specific exemption allowing the body to move into closed session, and the recording of a roll-call vote, with a majority of board members voting in favor of moving into closed session.

Among exemptions that would allow the body to move into closed session, Waterman listed the following purposes:

- • Judicial or quasi-judicial matters, defined as deliberations concerning a case which is subject to any judicial or quasi-judicial trial or hearing before the body.

- • Discharge/discipline, where the body is considering the dismissal, demotion or discipline of a public employee. The exemption stipulates that the public employee be given advance notice of the meeting and offered the opportunity to exercise his or her right to have the meeting conducted in open session.

- • Compensation and evaluation, defined as considerations involving employment, promotion, compensation or a performance evaluation of a specific public employee.

- • Competitive bargaining, defined as deliberations or negotiations for the purchase of public properties, investing public funds or other specific public business “whenever competitive or bargaining reasons require a closed session.”

- • Potential damage to a reputation, defined as the consideration of financial, medical, social or personal histories or disciplinary data of specific persons, whereby, if discussed in public, the information would “be likely to have a substantial adverse effect upon the reputation of any person referred to in such histories or data.”

- • Conferring with legal counsel concerning strategy with respect to litigation in which the body is likely to become involved.

- Once the body has convened in closed session, it may discuss only those items that are statutorily exempt from open session and were announced in open session by the presiding officer.

According to the workshop handout, governmental bodies can take final action within a closed session meeting under certain circumstances.

Under “guidelines for determining the appropriateness of voting in closed session, the handout enumerated the following: (a) the governmental body must have convened itself into a proper closed session, (b) the same reason for convening itself into closed session must apply to the need to vote in closed session, and (c) mere convenience in voting in closed session is impermissible.

The handout instead advised: “The better practice is to notice a meeting to convene in open session, adjourn to closed session and then reconvene into open session for action.”

As a matter of meeting notice requirements, the handout stated that notice of all meetings, open and closed, should be given as required by any other statute and “to the public; to those news media who have filed a written request for such notice, and to the official newspaper, or if none exists, to the news media most likely to give notice in the area.”

Notice should be made generally at least 24 hours prior to the meeting, and in an emergency, at least two hours in advance of the meeting, the handout stated.

Information about public records law and school board operations, as presented by Waterman during the workshop, will soon be published.

To learn more about Buelow Vetter, visit the firm’s website: https://buelowvetter.com.

A second part of this three-part story, including focus on Wisconsin’s public records law, is here: https://whitewaterwise.com/wusd-board-of-eduction-members-attend-workshop-review-open-records-law/.

Attorney Brian Waterman of the Waukesha-based firm Buelow Vetter Buikema Olson and Vliet, LLC (Buelow Vetter), prepares to conduct a workshop focused on open meetings and public records laws, and school board operations. The workshop was conducted Monday, July 10, in advance of the Whitewater Unified School District Board of Education’s regularly scheduled monthly meeting. Kim McDarison photo.

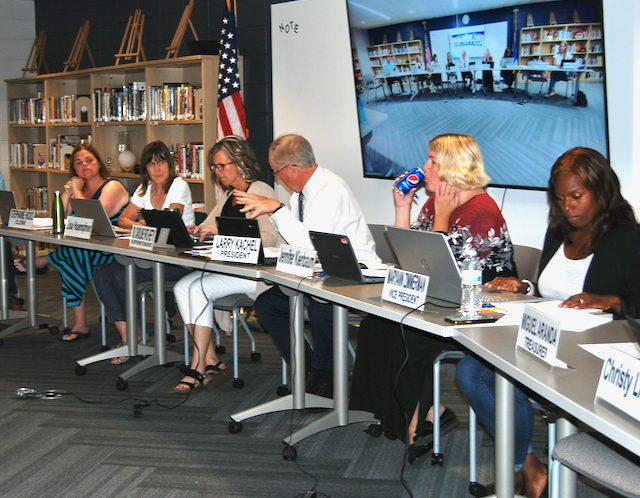

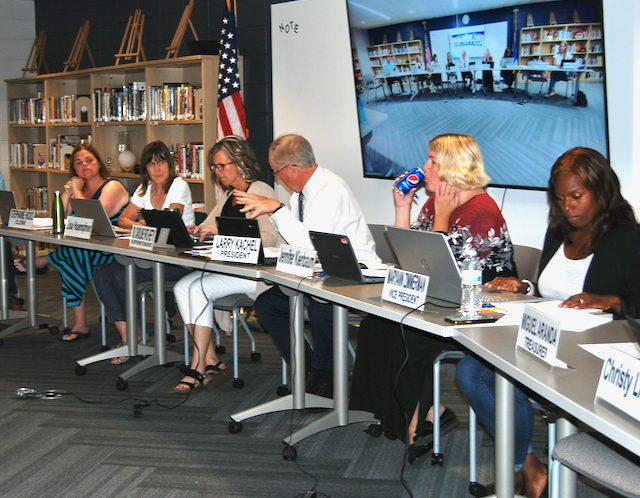

Members of the Whitewater Unified School District Board of Education, including Stephanie Hicks, from left, Lisa Huempfner, district Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty, board President Larry Kachel, Jennifer Kienbaum and Maryann Zimmerman, prepare to participate in an hour-long workshop focusing on open meetings and public records laws, and school board operations. Although not pictured, board member Christy Linse also was in attendance. Board member Miguel Aranda was in attendance for a portion of the workshop. Kim McDarison photo.

This post has already been read 943 times!

Kim

Our Advertisers

Most Read Posts

- No results available